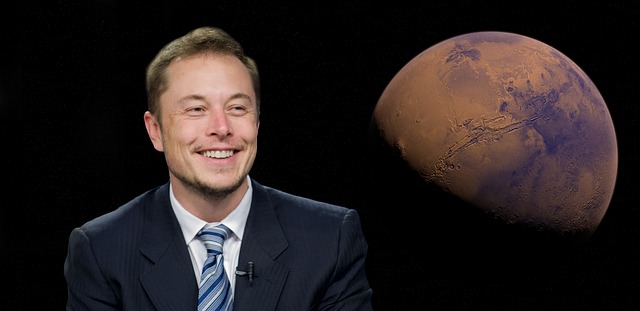

Elon Musk is at odds with the state of Delaware. “Never register your company in Delaware,” wrote the American billionaire in a message on X on January 30th. And he demonstrated that he practices what he preaches as two of his companies, Neuralink and SpaceX, announced that they would no longer have their fiscal headquarters in Delaware. In mid-February, it was revealed that Neuralink – which works to connect human brains to computers – would register its legal domicile in Nevada (where it already has its headquarters X, another Musk company), while the aerospace company SpaceX will be reconstituted in Texas.

At the end of January, a judge in Delaware overturned the compensation package that Musk was going to receive from the $56 billion company, the largest payment ever made to a CEO of a publicly traded company. The decision came from a lawsuit filed by shareholders who considered that Musk’s payment was excessive and the judge agreed with them. From there, Musk began his campaign to convince other companies not to establish their legal domicile in Delaware. His battle, however, seems uphill because this small state has been a very attractive place for the business sector for decades. In Delaware, more than 60% of the companies that make up the Fortune 500 index, which includes the 500 largest American corporations, are registered. We are talking about giants like Google, Amazon, Facebook, LinkedIn, Visa, MasterCard, or Walmart, among many others. In fact, in this state, more than 1.6 million companies from all over the world have their legal headquarters. But how is it possible that in this small state of barely a million inhabitants it has come to be known as the “world capital of shell companies”?

With an extension of just 5,000 square kilometers (similar to Trinidad and Tobago), Delaware historically never stood out for its economic potential. “Like now, early 20th-century Delaware was not well-known. The state maintained a small services sector and an even smaller industrial base. With no real natural resources or tourist attractions, the state survived by trying to absorb businesses from those traveling between New York and Washington, D.C.,” says Casey Michel in his book “American Kleptocracy: How the U.S. Created the World’s Greatest Money Laundering Scheme in History). The fate of this small state changed, however, in the early 20th century when then New Jersey governor (and future U.S. president) Woodrow Wilson put an end to the deregulatory policies that had made his state the most attractive place in the United States to start a company, thanks, among other reasons, to the fact that they were not even required to operate in their territory. “Delaware was in a perfect position to take advantage of New Jersey’s decision. The state enjoyed many of the same geographical advantages as New Jersey, located between the financial (New York) and political (Washington, D.C.) capitals of the United States,” points out Michel in his book. Delaware not only took the baton, but soon began to apply new and audacious reforms that turned that state into a true magnet for companies. Among the measures adopted, Delaware exempted corporations from paying state taxes and authorized them to reimburse their directors for expenses incurred in defending themselves legally from the claims of a shareholder. But also, according to Michel, Delaware had a key advantage to maintain its status as a leader as a global extraterritorial center: the Delaware Court of Chancery.

It is the oldest commercial court in the United States. It was created in 1792 and since then has been an inexhaustible source of case law specializing in corporate law. “The Court of Chancery turned out to be a key weapon in Delaware’s pro-corporate arsenal, a tool that no other state could match. As a couple of American academics discovered, this state-level court has provided ‘expert judicial power and an ability to quickly resolve complex commercial disputes,’ effectively providing Delaware with a much deeper source of corporate case law than any other state in the country,” says Michel. But if all these advantages were not enough, the facilities offered by that state to register a company are hard to beat. For just $1,000, it is possible to register a company in just one hour. This time can even be reduced to half if you want to pay an additional $500. In addition, these procedures can be done online, without the need to set foot in Delaware. So, it is not surprising that every day about 683 companies are registered in Delaware on average. And that state gets great benefits: every year it receives about $1.5 billion from the companies registered there.

Among the facilities offered by Delaware to create companies, there is one, in particular, that has made this state the subject of numerous criticisms: the possibility of establishing a company anonymously. “We don’t need to say that we are the owners of the company. We can anonymously create a limited liability company [LLC]. And we don’t have to show any kind of identification in order to establish it,” explained Hal Weitzman in the Big Brains podcast of the University of Chicago. Weitzman is a professor at that university and author of the book “What’s the Matter with Delaware? How the First State Has Favored the Rich, Powerful, and Criminal – and How It Costs Us All.” Most (70%) of the companies registered in Delaware each year are LLCs and, according to Weitzman, this is influenced by the state’s policy of not requesting information that identifies the owners “because these LLCs do not have to report anything to anyone.” This possibility of anonymity has made Delaware a very attractive place to register companies that are then used in all kinds of illegal operations around the world. And the consequences of this affect many other places, as according to experts, many times those who want to launder money from illegal activities anonymously create a shell company in Delaware and then through this acquire or invest in other companies in another state and/or another country without anyone finally knowing who the real owners or beneficiaries are. “The examples are too numerous to count. International criminals and corrupt foreign officials, arms smugglers and rhino poachers, human traffickers… all of them look to Delaware,” says Michel in his book, referring to Delaware as “the greatest source of anonymous shell companies the world has ever seen.” Among the dubious characters who have resorted to Delaware companies to hide questionable operations are the Russian Viktor Bout, known as “the merchant of death,” one of the most well-known arms traffickers in the world.

“Finding clients and partners from Central America to Central Asia, from warlords in sub-Saharan Africa to people working closely with the Taliban, Bout conducted almost all major illicit arms transfers in the shadows during the 1990s and early 2000s. Combat aircraft and anti-aircraft weapons, machine guns, and machetes: the products didn’t matter. The only thing that mattered was moving the merchandise to waiting customers and making sure that those who investigated him, including U.S. officials, never discovered the financial networks that facilitated Bout’s arms trafficking work,” says Michel. Two of the shell companies Bout used for his operations were registered in Delaware. But not only major international criminals use shell companies in Delaware to hide questionable operations. In 2016, Michael Cohen, then Donald Trump’s lawyer, registered two companies in Delaware that he used to process payments made to adult film actress Stormy Daniels